It was a weekend, in the night, like it always is; the patient, a 32yo narcotic addicted woman who’d been filling her Vicodin from a pain doctor in another city in another state for her upper abdominal pain for the past week. I’m not saying I don’t understand. Chronic pain patients always have pain—that’s why it’s chronic, and if you’ve already crossed the Rubicon of starting a patient on narcotics for long-term management of pain, it is a slippery slope and difficult to stop, which is why I don’t do it; but, I’m not a pain doctor. I’m a Surgeon. Thank God….most days, this night not being one of those.

The ER called me on Saturday, or was it Sunday? I can’t remember it now; but it was late and a poor scrub tech volunteered for four hours of hell. Had they known it was going to be four hours of hell, you might think she wouldn’t have come in; but she would have, because that’s what they do, and they’re good; every last one of them. “She’s febrile, has peritonitis and gas in the wall of the gall bladder and her white count is 24k.” The voice, low, urgent, whispered through the phone across the darkness of night as though he were Charon summoning me from across the river Styx.

She was toxic, with a surgical abdomen and a dead, gangrenous gallbladder full of pus. She needed six inches of cold steel, which is my pet name for scalpel. She needed six inches of cold steel six days ago. It was 11:15pm by the time Anesthesia, the circulator, and the volunteer tech arrived; three people, not including me. It was 3:30am when three people went home. One stayed. Guess who?

I knew it was going to be bad, but I still started out laparoscopically. Maybe I’m overly optimistic, at least my anesthesia friend always says I am habitually so; but, it is the standard of care, and maybe I’d get lucky.

I wasn’t lucky, and I knew I wasn’t lucky inside of the first ten minutes. The gallbladder was mottled black and thick-walled and friable and that was when I could find it because it was socked in and covered by the fatty omental tissue that’s supposed to hang down in front of the abdomen and protect the small bowel and viscera. The problem is, when something gets infected and inflamed, it gets sticky, and things stick to it, like the omentum and other adjacent structures, like the colon and duodenum. The hallmarks of inflammation are pain, redness and swelling; and if you add in infection it just gets even worse.

Thirty minutes into the case, twelve to eighteen inches deep in the patient’s right upper quadrant, I didn’t feel any better. I had managed to find the gallbladder and separate it from the colon and omental tissue, but about three fourths of the way down, in the area of what I felt to be the neck of the gallbladder, it disappeared into a solid chunk of phlegmon, which means infected tissue. It was like a chunk of pink, vascularized tissue without any planes of separation. Imagine a chunk of soft, pink rubber that bleeds when you cut it.

The gallbladder was rotten and I couldn’t staple across it and call it a day and wait several weeks for the infection to clear. I could have put a drain in and done some temporizing, but most of the time, in cases such as these, you just begin at the beginning, and go on until you come to the end: then stop—like the King said in Alice in Wonderland; a series of baby steps; baby steps with patience, baby steps with anxious expectation, and, baby steps with fear.

Two hours in, I think I can see the cystic duct, and it’s alive, which means I can tie it, clip it, control it. Now I need the cystic artery. I start separating the gallbladder from the liver on top. That’s called retrograde dissection. The idea is to completely separate the gallbladder from the liver so that the only thing attaching it to the patient then is the cystic duct and cystic artery. Problem in this case was the chunk of vascularized rubber thing. It was hard to tell where the liver stopped and the gallbladder began. Still, I tried, and actually had a modicum of success. I was down to about an inch-and-a-half of tissue between a rotten gallbladder and all sorts of important stuff, mainly the common bile duct and hepatic artery.

Half-an-hour later, with my scalpel, dissecting one cell layer at a time (I’m sure), I think I see the cystic artery; but then it’s gone, lost in sudden pool of blood. I’m not sure if I heard it or if I imagined the roaring in my ears. The suction can barely keep the rising pool of blood level. I say dang it a few times and let the anesthesiologist know that the patient is bleeding and that I don’t have control. I have the tech suction and I use the forceps and a lap sponge to compress and possibly reveal the source of bleeding for me to place a suture or a clip. But I can’t. I hear bodies moving around the OR, frantic voices and then anesthesia says, “You’re going to have to do something. I can’t keep up much longer.”

I place a dry lap sponge in the hole and hold pressure and remember…

Nik Luiz, a double first name: His last name was long gone down the memory hole because he insisted on being called by his first name, rather than doctor (last name)–as a third-year resident, I never got used to it. Nik Luiz was helping me do one of my first gallbladders, back in the day before laparoscopic cholecystectomies were invented. He was a foreign medical graduate on a two-year commitment at the military hospital where I was six weeks into an eight-week rotation on the surgery service. I thought he was okay, but it was clear that his surgical skills were not at the level of the other surgical staff.

Our patient was a sixty-some-year-old male with acute cholecystitis. It wasn’t that bad—I could see the cystic duct and artery. Because of the swelling and inflammation I had taken the gallbladder down retrograde because I wasn’t convinced about the anatomy, and we both thought that it made sense. Nik Luiz was retracting (holding) the gallbladder by a couple of large clamps while I was placing the ligatures around the cystic duct; two ties of 2-0 silk; there, cut between the two with the Metzenbaum scissors.

I hear Nik Luiz’s surprised voice, “specimon?” And I look over to the gallbladder swinging from the clamps. Then I look back into the wound at an audible gurgle of red, rising. Then Nik Luiz see’s it too, his face blanches, and there’s white all around his dark eyes. He pushes me aside, shoves a lap sponge in the wound and screams, “Call Bucky!”

Direct pressure will stop nearly all bleeding. If it doesn’t, the patient dies shortly. What had happened was that after I had cut the cystic duct, there was nothing but a two to three millimeter vessel connected to the gallbladder which Nik Luiz promptly avulsed from the common hepatic artery and what was left was an equivalent-sized hole in the side of the major artery carrying blood to the liver. I should have been controlling the amount of traction, but I wasn’t, guess I hadn’t learned that yet.

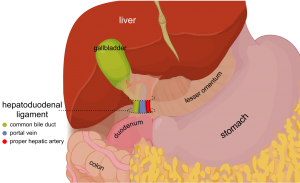

Bucky was a junior staff from one of the southern states. He was standing next to me in what seemed like less than a minute, listening to Nik Luiz’s explanation. He said, “Did you try a Pringle maneuver?” Nik Luiz didn’t say anything. I knew what it was, but must admit it didn’t occur to me in the moment. Bucky explained, “we have to compress the hepatoduodenal ligament proximal to the injury to control the bleeding so then we can repair the vessel,” he turned to the nurse, “we’ll need some 3-0 or 4-0 prolene, quickly.”

Bucky motioned me to the left side of the table and, using his right hand, he placed my left hand where his left hand was, pinching the hepatoduodenal ligament, a thick wide band of tissue between the first part of the small intestine just after the stomach and the central part of the liver called the hilum. It is where the common hepatic artery, common bile duct and portal vein run—all vital structures. The cystic duct is a side branch off of the common bile duct, and the cystic artery is a side branch off of the hepatic artery. By compressing the ligament, all of the structures are occluded. Since the cystic artery’s take off is further up on the hepatic artery, if you compress the hepatic artery below it, the bleeding should stop.

“Feel where my fingers are, three fingers behind and the thumb on top?”

“Yes.”

“Good. Now you place yours there, just above the duodenum and squeeze.” The bleeding stopped…

I see Bucky, as clear as the day we last met, ageless, like an angel in the room. Two to three minutes pass. The patient’s blood pressure has climbed into the 90’s after a unit of blood, maybe two. I place my hand into the hole and by feel, find the hepatoduodenal ligament, three fingers under, my thumb on top and squeeze. It’s like I’m going backwards in a Feynman diagram as the continuum of past and present meld transiently into a dual presentation of similar moments separated by what seems a lifetime. I pull the lap sponge out.

The bleeding stops.

I see a small tear, or an opening above where my fingers are. I relax my grip slightly and blood wells up. I squeeze again.

I turn my head towards the scrub nurse, “Sandy, I’m going to need some 4-0 prolene and a vascular clamp.”